Introduction

Phenolic resins – past, present and future…

…has a renaissance arrived for the first-ever synthetic polymer?

Paul Ashford, Anthesis-Caleb

Regulatory and marketing advisors to the European Phenolic Resins Association (EPRA)

An enviable past

It’s already over ten years ago that the phenolic resins community celebrated the centenary of a Belgian national, Leo Hendrik Baekeland discovering the societal value of reacting phenol with formaldehyde to form a phenolic resin. The event was marked in September 2007 by a symposium organised by the University of Ghent which was the place where Baekeland completed his doctorate and taught for several years.

The European phenolic resins industry was well represented at the event which was partially sponsored by both the European Phenolic Resins Association (EPRA) and the then newly-formed Global Phenolic Resins Association (GPRA).

The European phenolic resins industry was well represented at the event which was partially sponsored by both the European Phenolic Resins Association (EPRA) and the then newly-formed Global Phenolic Resins Association (GPRA).

However, what has become of the technology which Baekeland had invented after he sold it to Union Carbide on his retirement in 1938? This article seeks to explore that question and highlight where phenolic resins might be going in future.

Jack of all trades…

There are significant advantages to being “first on the block”! Bearing in mind that there had been naturally sourced resins (e.g. Shellac) for many years prior, there were already well-established markets for the product. However, not even Baekeland could have predicted the breadth of application for which his invention ‘Bakelite’ was to become used – particularly when used in the form of a moulding powder.

“A thousand uses” was probably no exaggeration as the introduction of ‘Bakelite’ coincided with the burgeoning growth of demand for electrical goods as well as more traditional items such as cookware.

Today, it seems rather ironic that the sheer success of ‘Bakelite’ has caused it to be associated with a by-gone age even to the point that it has more recently been an icon of the ‘retro’ movement. However, far from being a thing of the past, phenolic resins were only just beginning to have their real potential recognized.

…master of several!

As competitive materials began to emerge – initially in the guise of other synthetic thermosetting resins (e.g. epoxy) but later with cheaper, oil-based thermoplastics, it became clear that phenolic resins should be focused on applications for which their specific properties where best suited. These properties were identified as being their high temperature resistance and their adhesive qualities. The following list of applications has therefore become synonymous with the present day phenolic resins market:

Construction

- Plywood adhesives

- Binders for mineral wool insulation

- Insulating foams

- Decorative laminates

- Components for contemporary adhesives

- Abrasives

Transport

- Under-bonnet uses (moulding compounds)

- Friction materials for brakes and clutches

- Fibre-reinforced composites

- Foundry and refractory resins

- Rubber reinforcing resins

Household Appliances & other Articles

- Kitchenware (moulding compounds)

- Can coatings

- Ink formulations

- Electrical laminates

On the basis of these core activities the use of phenolic resins has grown consistently through the decades following sale of Baekeland’s business to Union Carbide. Demand has varied according to region, with probably the best example being the dominance of the plywood adhesives use in North America where timber-framed building techniques remain prevalent and highly reliant on stable and water-resistant binders.

On the basis of these core activities the use of phenolic resins has grown consistently through the decades following sale of Baekeland’s business to Union Carbide. Demand has varied according to region, with probably the best example being the dominance of the plywood adhesives use in North America where timber-framed building techniques remain prevalent and highly reliant on stable and water-resistant binders.

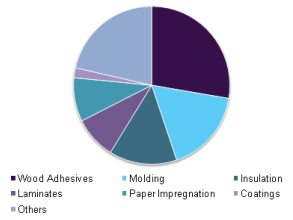

According to a range of market research sources, the global market for phenolic resins had reached close to 5 million tonnes in 2015 with a value in excess of $10 billion. Use patterns were estimated to be as follows:

More importantly, most market assessments have been predicting a CAGR of >5% in the period through to 2021, indicating that core market fundamentals for the industry remain strong.

Trade between regions usually represents less than 10% of total demand, reflecting the fact that it is not usually considered cost-effective to transport resins (particularly liquid resins) over long distances. Therefore, regional production closely parallels demand in most cases. Where leading-edge technology is required all around the world (e.g. in friction materials or rubber reinforcing resins), it has been common-place to see licensing agreements springing up to accommodate such transfer. However, in more recent years, a number of truly global manufacturers have emerged and these are able to transfer technologies internally.

At the regional level, EPRA’ own data supports the global trends observed by the market researchers. The Association covers over 90% of the European non-captive market with the exception of foundry resins. Based on its detailed statistics gathering, EPRA reports a market of over 800,000 tonnes/annum with overall activity up 6.1% in 2017. Particularly strong growth has been reported in the construction sector with mineral wool binders up 7%, wood binders up 8.2% and insulation foam resins up 13.3%, albeit from a lower base.

Fire Properties as a further driver

Stepping back to the broader drivers for uptake of phenolic resins, in the latter part of the 20th century some of the short-comings of the cheaper, thermoplastics route began to emerge, particularly in respect to fire and smoke. A series of high profile fires in Europe and elsewhere threw attention onto the need for materials demonstrating all of the advantages of polymeric materials but without the drawbacks of the established incumbents.

It was on the back of this demand for higher performance materials that the phenolic industry launched an array of products based in the excellent intrinsic fire performance of the phenolic matrix (low flame spread and extremely low smoke emissions). Among these, phenolic foams and fibre reinforced phenolic composites are perhaps the most well-known.

Phenolic foam has been particularly successful in parts of Europe where the fire performance of core materials or exposed elements has been paramount. This aligns with even more significant growth of phenolic foam use in Japan, where population density and building methods make phenolic insulation an obvious choice.

Has the anticipated renaissance arrived?

Ten years ago, in a similar article to this, the author speculated that a renaissance in the use of phenolic chemistry might be on the way. Certainly the evidence of the intervening years shows that the competitive positioning of phenolic resins has largely improved, despite the impact of the financial crash in 2008-09 and the growth in competition in a number of sectors (see next paragraph). It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that a renaissance has well and truly arrived.

With the myriad of competitive materials now in the market place, there are usually one or more competitive options available for most applications. However, because the global phenolic resins market went through such a substantial refining process in the mid 20th century, the current application portfolio has remained remarkably robust, and is only significantly influenced if the application itself comes under threat. Part of the reason for this has been the continuing development and refinement of the technology.

Technical differentiation in a competitive world

As global chemical regulation has really taken hold over the last ten years, EPRA members have invested heavily in seeking to ensure compliance by increasing their understanding of the downstream user applications and the exposure scenarios related to them. This has been particularly relevant following the reclassification of formaldehyde and has led to the introduction of ultra-low free formaldehyde resins which have been well-received in a number of sectors.

Perhaps more importantly, the pressure to limit formaldehyde emissions has put additional focus on the fact that the phenol-formaldehyde bond is very stable and does not hydrolyse. This ensures minimal formaldehyde emissions throughout the lifecycle of the cured articles which is an increasingly important factor in the construction sector as indoor air quality standards continue to increase.

In conclusion

Phenolic resins have demonstrated themselves to be unique over more than a century of usage – no other polymer can yet make such a claim! Baekeland would be very proud of that fact, but I doubt that he would be resting on his laurels. He would be off finding the next groundbreaking use for his invention!

Moreover, Baekeland would be very gratified to see that his material had undergone something of a renaissance with the key characteristics of the chemistry differentiating phenolic resins from other materials in a way which continues to deliver unique value to society.

EPRA members have a responsibility to ensure that this renaissance continues and are investing significantly to provide the assurances that an ever more demanding client base requires. This includes the evidence to properly describe the inert character of the fully-cured matrix which has been in our midst as Bakelite for over 100 years.

Paul Ashford – March 2018